article Adverse Childhood Experiences

What are ACEs?

The term “ACEs” originated in a 1998 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a Kaiser Permanente study that found significant linkages between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and a range of negative health outcomes. ACEs are potentially traumatic experiences, such as neglect, experiencing or witnessing violence, and death or illness in the family. Tools to assess for exposure to ACEs and trauma include a series of questions to identify a person’s experiences before age 18.

Impact of ACEs

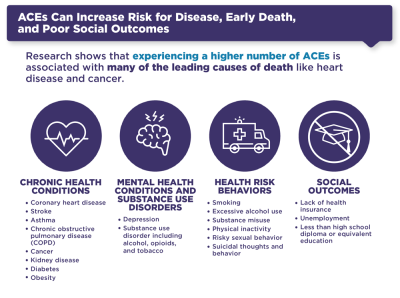

The impact of childhood trauma appears to increase with the accumulation of a higher number of ACEs. Current research indicates that individuals with four or more ACEs are two to five times as likely to develop clinical depression, serious emotional disturbance, substance use disorders, suicidal ideations and attempts, and numerous chronic health conditions, including diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases compared to those with no ACEs1.

The impact of ACEs is evident across the lifespan. In children, high ACE scores contribute to the risk of anxiety and depression, developmental delays, negative cognitive and socioemotional health issues, academic challenges, behavioral health issues, and specialized health needs1. ACEs also impact education and financial prospects—ACEs decrease the likelihood of high school completion and college degree attainment and increase the likelihood of unemployment, living in poverty, and experiencing homelessness1.

Risk Factors

Individual, family, and community factors can impact the likelihood of ACEs. While most ACE assessment tools focus on a child’s household, other adverse experiences, such as bullying, teen dating violence, and community violence, may occur outside the home. Additionally, experiencing some ACEs can increase the risk of experiencing other ACEs2. For example, families with low income are more likely to live in communities with high rates of poverty, food insecurity, and unstable housing, potentially compounding a child’s experiences of traumatic stress.

Children living in poverty, including those experiencing homelessness, are more likely to carry high ACE scores, increasing their risk of developmental challenges and poor health and functioning. The experience of poverty may affect the structures and functions of developing brains, including reduced synapses and cortical size, which affect cognitive processes and behaviors. Poverty has been shown to affect the functions of the prefrontal cortex, impacting language, executive functioning, attention, and memory3.

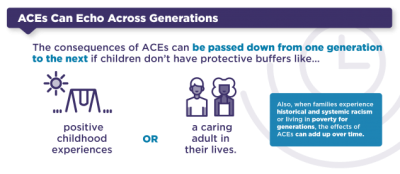

Trauma also affects an individual’s gene expression, which can impact both the individual and their offspring. Through epigenetics, biochemical processes activate or deactivate specific genes, so the adversities an individual faces, such as chronic stress, take a toll on the body and accelerate physiological aging4.

Individual and Family Risk Factors |

Community Risk Factors |

|---|---|

|

|

Resiliency

Resilience is the ability of an individual to withstand threats to stability in the environment.

Resilience builds over time as an individual develops, and ACEs can alter their capacity for resilience, making it harder to respond to crises in adulthood.

The human brain grows and changes across the lifespan. There are periods of rapid development (particularly during the prenatal, neonatal, early childhood, and adolescence periods) when the brain is especially susceptible to being shaped by adverse experiences. Research indicates that the timing of ACE exposure affects health outcomes; children who only experienced elevated ACE exposure between the years of 0-3 experienced outcomes similar to children with consistently high ACE exposure, regardless of the cumulative difference, and children with decreasing exposure exhibited higher resilience5.

The concept of plasticity also suggests that interventions for adverse experiences can be effective; positive experiences can shape and affect the brain just as adverse ones can. Having supportive relationships and a supportive environment can impact how the body responds to chronic stress. According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, the most common factor for children who develop resilience is having at least one stable relationship with a supportive parent, caregiver, or other adult6. These relationships provide the personalized responsiveness, structure, and protection that buffer children from developmental disruption. They also build critical capacities—such as planning, monitoring, and regulating behavior—that enable children to adapt to adversity and thrive. This combination of supportive relationships, adaptive skill-building, and positive experiences is the foundation of resilience.

Like risk factors, protective factors can exist within the household and the broader community.

Additional Resources

Understanding Child Trauma [HTML] | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Recognizing and Treating Child Traumatic Stress [HTML] | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Get Help Now [HTML] | The National Child Traumatic Stress Network

[1] National Healthcare for the Homeless Council and National Network to End Family Homelessness. 2019. "Homelessness and Adverse Childhood Experiences." https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/aces-fact-sheet-1.pdf.

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023. Risk and Protective Factors. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/riskprotectivefactors.html.

[3] Lipina, Sebastian J, and Michael I Posner. 2012. "The impact of poverty on the development of brain networks." National Library of Medicine. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2012.00238.

[4] Sullivan, Shannon. 2013. "Inheriting Racist Disparities in Health." Critical Philosophy of Race 190-218.

[5] McKelvey, Lorraine M, Nicola A Connors Edge, Shalese Fitzgerald, Shashank Kraleti, and Leanne Whiteside-Mansell. 2017. "Adverse childhood experiences: Screening and health in children from birth to age 5." Families, Systems, & Health 420-429.

[6] Harvard University Center on the Developing Child. 2023. Resilience. Accessed August 25, 2023. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/resilience/.

Recent Articles

Classification

- Focus

- Age: Children, Youth

- Topic

- Mental Health: Serious Emotional Disturbance, Serious Mental Illness, Mental health treatment; Trauma

- Language

- English